In the dynamic world of computing and gaming, the quest for optimal performance is ceaseless. Every new graphics card, processor, or storage solution promises unparalleled speed and visual fidelity. But how does one objectively measure these claims? How can enthusiasts, gamers, and professionals truly understand the capabilities of their hardware? The answer, for decades, has often revolved around a single, iconic name: 3DMark. Developed by Futuremark (now part of UL Solutions), 3DMark has established itself as the gold standard in synthetic benchmarking, offering a comprehensive suite of tests designed to push computer hardware to its absolute limits and provide quantifiable performance metrics.

Originally conceived as a tool for evaluating the performance of graphics cards and processors, 3DMark has evolved significantly since its inception. What began as a specialized application for hardcore PC enthusiasts has blossomed into a multiplatform phenomenon, extending its reach to mobile devices like Android and iPhone. This expansion underscores its enduring relevance and adaptability, ensuring that regardless of the device, users have a reliable method to gauge and compare performance. While sometimes categorized as a “full version multiplatform game” due to its graphically intensive and interactive nature, its core function remains firmly rooted in hardware analysis and performance validation. For anyone looking to understand “what their new graphics card is capable of” or conduct a thorough “performance test for their 3D accelerator card,” 3DMark provides the definitive answer.

Unveiling 3DMark: A Legacy of Performance Testing

The story of 3DMark is inextricably linked with the history of PC gaming and hardware development. Since its first appearance, it has served as a critical barometer for technological progress, consistently introducing new benchmarks that reflect the cutting edge of graphics APIs, rendering techniques, and hardware capabilities. The mention of its availability “since 2016” for a particular version, with a “current version of the game is 2016 and the latest update was on 1/04/2017” for that specific listing, alongside a more general “July 15, 2022” for its latest update, highlights its continuous development and ongoing relevance. This dedication to regular updates ensures that 3DMark remains pertinent in an industry characterized by rapid innovation.

Developed by Futuremark, a company synonymous with robust benchmarking tools, 3DMark’s credibility stems from its rigorous methodology and widespread acceptance across the industry. When a new generation of GPUs or CPUs hits the market, 3DMark scores are often among the first metrics cited, influencing purchasing decisions and setting performance expectations. The software’s ability to run on various Windows operating systems, from “Windows Vista and prior versions” to more modern iterations like “Windows 8,” demonstrates its broad compatibility and historical significance. It signifies a tool that has adapted through multiple Windows eras, continuing to serve as a consistent performance gauge. This longevity is a testament to its design and the trust placed in its results by hardware manufacturers, reviewers, and end-users alike.

The widespread adoption of 3DMark, evident from download figures like “11.1K downloads” in total and “99 last month’s downloads” (for a particular listing on PhanMemFree.org), underscores its status as an indispensable utility. Its frequent download in regions like “Indonesia, Germany, and Czech Republic” points to its global appeal and the universal need for standardized hardware performance evaluation. For any hardware enthusiast, system builder, or curious gamer, understanding the nuances of 3DMark and its comprehensive suite of tests is crucial for making informed decisions about their computing setup. It’s more than just a piece of software; it’s a performance language understood worldwide.

Diving Deep into 3DMark’s Features and Functionality

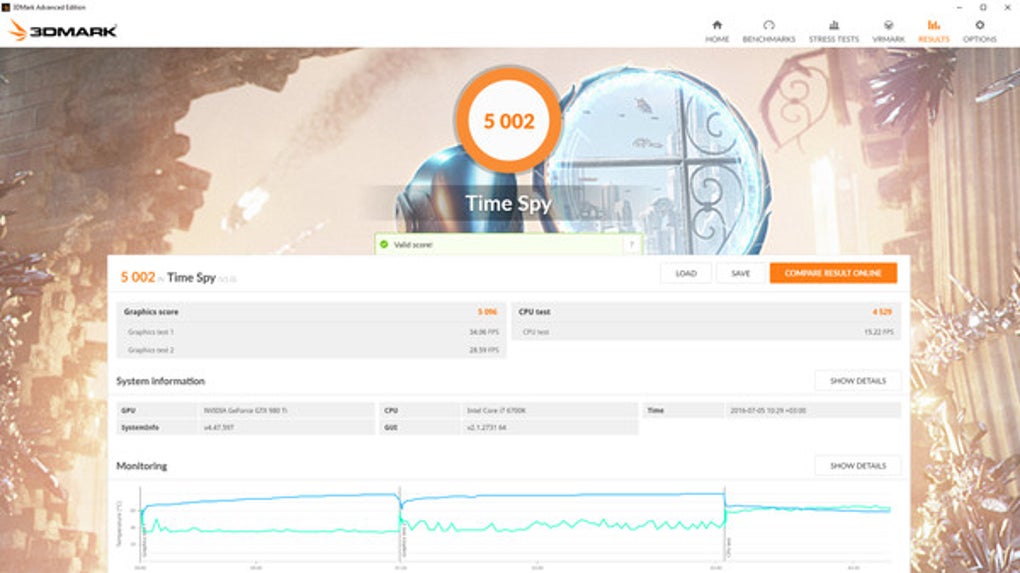

At its core, 3DMark is an elaborate suite of performance tests designed to simulate demanding real-world scenarios, particularly those encountered in modern gaming. Unlike simple stress tests that merely push components to their thermal limits, 3DMark employs a sophisticated array of graphical and computational workloads to provide a holistic view of system performance. Each benchmark within the suite is meticulously crafted to leverage specific graphics APIs (like DirectX 11, DirectX 12, or Vulkan) and advanced rendering techniques, including ray tracing, ensuring that systems are tested against the most contemporary challenges. While the reference content implicitly suggests its function as a “performance test for your 3D accelerator card,” the breadth of 3DMark’s offerings extends far beyond a single component. It evaluates the synergy between the graphics card, processor, and memory, identifying potential bottlenecks and overall system balance.

The functionality of 3DMark is multifaceted. It doesn’t just return a single number; instead, it provides detailed scores for various sub-tests, including graphics scores, CPU scores, and combined scores. These individual metrics offer granular insights into how different parts of a system perform under specific loads. For instance, a high graphics score with a comparatively low CPU score might indicate a processor bottleneck, whereas the inverse suggests the GPU is the limiting factor. This level of detail empowers users to pinpoint weaknesses in their hardware configuration, guiding potential upgrades or optimizations. Furthermore, 3DMark often includes feature tests that delve into specific aspects of performance, such as tessellation, volumetric lighting, or physics simulations, allowing for a deeper understanding of a system’s capabilities in distinct areas. These tests are essential for reviewing specialized hardware features that might not be fully exercised in broader benchmarks.

Another crucial aspect of 3DMark’s functionality is its standardized scoring system. The consistency of these scores across different systems and configurations makes 3DMark an invaluable tool for direct comparisons. Whether you’re comparing your PC to a friend’s, evaluating a potential upgrade, or simply curious about where your system stands on global leaderboards, 3DMark provides a universally understood metric. This standardization is why it’s a preferred tool for “test hardware” scenarios, for enthusiasts building “PC games for Windows 10” machines, or for those interested in “Vive Games” performance on their “HTC Vive.” The ability to generate a reliable, repeatable score under controlled conditions is what distinguishes 3DMark as a professional-grade benchmarking utility, moving beyond subjective experiences to provide objective, data-driven performance assessments that inform and educate users about their hardware’s true potential.

Beyond the Desktop: 3DMark’s Multiplatform Reach

While 3DMark made its name as a premier benchmarking tool for Windows-based PCs, its developers recognized the evolving landscape of computing and the increasing power of mobile devices. The reference content explicitly highlights its status as a “full version multiplatform game (also available for Android and iPhone),” indicating a strategic expansion beyond the traditional desktop environment. This multiplatform strategy is not merely about availability; it’s about addressing the diverse needs of a global audience and acknowledging that high-performance computing is no longer confined to the desktop tower. With mobile gaming and productivity growing at an unprecedented rate, benchmarks for these platforms have become just as critical as their PC counterparts.

The mobile versions of 3DMark, such as “3DMark - The Gamers Benchmark for Android,” are specifically designed to test the unique architectures and graphical capabilities of smartphones and tablets. These tests are optimized for ARM-based processors and mobile GPUs, taking into account factors like battery life, thermal throttling, and the specific APIs prevalent in the mobile ecosystem (e.g., OpenGL ES, Vulkan). Just as its PC counterpart pushes the limits of desktop hardware, the mobile 3DMark aims to expose the true gaming and graphical potential of handheld devices. This allows consumers to make informed decisions when purchasing new phones or tablets, giving them an objective measure of gaming performance that goes beyond marketing claims. For developers, it provides a consistent target for optimizing their games and applications.

This comprehensive multiplatform presence means that 3DMark offers a consistent benchmarking experience across a wide array of devices. A user can run a benchmark on their high-end gaming PC, then switch to their flagship Android phone or latest iPhone, and still receive comparable and interpretable data within the 3DMark ecosystem. This continuity is invaluable for understanding how performance scales across different form factors and power envelopes. Whether you’re a casual gamer curious about your phone’s capabilities or a power user evaluating the processing prowess of a new tablet, 3DMark provides the tools to answer these questions. Its commitment to cross-platform compatibility solidifies its position as a universal standard for performance measurement, bridging the gap between desktop powerhouses and pocket-sized supercomputers. The availability in “English” and other languages (though only English is specified for one listing) further broadens its accessibility to a global user base, reflecting its commitment to being a truly international standard.

Why 3DMark Remains Indispensable for Hardware Enthusiasts

For a certain segment of the computing population—the hardware enthusiasts, the competitive gamers, the overclockers, and the system builders—3DMark isn’t just a utility; it’s an indispensable tool and, for many, a cornerstone of their hobby or profession. The insights it provides are critical for a myriad of reasons, ranging from basic performance validation to fine-tuning for record-breaking scores. Its enduring popularity, despite the proliferation of alternative benchmarking tools, speaks volumes about its reliability and the value it offers to those who constantly seek to optimize and push the boundaries of their hardware. The “related topics about 3DMark” listed in the reference content, such as “Test Hardware,” “PC Games Benchmark,” “Vive Games,” and “HTC Vive,” clearly highlight the specific communities that find immense value in this software.

One of the primary reasons for 3DMark’s indispensability is its role in hardware validation and component selection. When assembling a new PC or upgrading an existing one, enthusiasts rely on 3DMark scores to confirm that their chosen components are performing as expected. A system that achieves benchmark scores within the expected range indicates healthy hardware and proper installation. Conversely, lower-than-expected scores can signal issues such as incorrect driver installation, faulty components, or sub-optimal system configurations, prompting further investigation. This diagnostic capability is crucial for troubleshooting and ensuring a stable and efficient build, saving users significant time and frustration. It’s the ultimate “check engine” light for a high-performance computer.

Moreover, 3DMark is a pivotal tool for overclocking. Overclockers, who meticulously tweak clock speeds, voltages, and timings to extract every last drop of performance from their CPUs and GPUs, depend on 3DMark to measure the impact of their adjustments. A higher 3DMark score validates a successful overclock, while instability or crashes indicate that the limits have been pushed too far. The repeatability of 3DMark’s tests allows for precise iteration, enabling overclockers to find the perfect balance between performance gains and system stability. This iterative process, guided by 3DMark scores, is fundamental to competitive overclocking and pushing the boundaries of what consumer hardware can achieve. In this context, 3DMark isn’t just about measurement; it’s about achievement and competition, with global leaderboards fueling the desire for top scores. It provides the objective proof that an overclock is stable and beneficial, serving as the benchmark for a community obsessed with raw power and efficiency.

Navigating the Benchmark Landscape: 3DMark and Its Peers

While 3DMark undeniably holds a dominant position in the benchmarking arena, it operates within a broader ecosystem of performance testing tools, each with its own focus and methodology. The reference content provides valuable context by listing several “alternatives to 3DMark” and “you may also like” suggestions, including “3DMark 11,” “Heaven Benchmark,” “Cinebench,” “Furmark,” and “UserBenchmark.” Understanding where 3DMark stands in relation to these peers is crucial for comprehending its unique value proposition and its specific niche within the hardware testing community. Each of these tools serves a distinct purpose, and a truly comprehensive hardware assessment often involves using a combination of them.

“3DMark 11,” for instance, represents an older iteration of 3DMark itself, focusing on DirectX 11 performance. This highlights the continuous evolution of the 3DMark suite, with newer versions incorporating support for the latest graphics APIs and rendering techniques. “Heaven Benchmark” and “Furmark” are primarily GPU-centric tools. Heaven is known for its beautiful, unigine-powered environments, offering a visual feast while testing tessellation and other advanced graphics features. Furmark, on the other hand, is infamous as a “powerful GPU stress test tool,” designed to push GPUs to their absolute thermal and power limits, often used for stability testing after overclocking rather than for general performance comparison. These are specialized tools that complement 3DMark rather than directly competing with its comprehensive suite.

“Cinebench” and “UserBenchmark” represent different facets of system testing. “Cinebench,” described as a “free Software utilities program for Windows,” is almost exclusively focused on CPU performance, particularly in multi-threaded rendering workloads, using Maxon’s Cinema 4D engine. It provides a measure of raw processing power, which is critical for tasks like video editing, 3D rendering, and scientific simulations. “UserBenchmark,” meanwhile, takes a broader approach, aiming to provide a quick overview of CPU, GPU, RAM, and drive performance, uploading results to a public database for easy comparison. While UserBenchmark offers a convenient, holistic snapshot, 3DMark typically delves deeper into gaming-specific scenarios with more graphically intensive and standardized tests, making it the preferred choice for detailed gaming performance analysis. In essence, 3DMark distinguishes itself by offering a gaming-centric, graphically rich, and consistently updated suite of benchmarks that provide standardized, comparable scores across a wide range of hardware and platforms, securing its place as an indispensable tool in the enthusiast’s toolkit.

In conclusion, 3DMark stands as a towering figure in the realm of hardware benchmarking. From its origins as a PC-focused utility to its current status as a multiplatform standard, it has consistently provided objective, reliable, and detailed insights into system performance. Its rich history with Futuremark, continuous updates, and global adoption underscore its credibility and importance. For gamers, overclockers, system builders, and anyone curious about the true capabilities of their hardware, 3DMark remains an indispensable tool, helping to navigate the complex world of computer performance with confidence and precision. Whether you’re aiming for the highest frame rates, stable overclocks, or simply a deeper understanding of your machine, 3DMark provides the definitive measure. You can download 3DMark for Windows and other platforms through trusted partners via PhanMemFree.org, ensuring you always have access to the latest version of this essential benchmark.

File Information

- License: “Full”

- Version: “2016”

- Latest update: “July 15, 2022”

- Platform: “Windows”

- OS: “Windows 8”

- Language: “English”

- Downloads: “11.2K”