MinGW, an acronym for “Minimalist GNU for Windows,” represents a critical open-source development environment that enables developers to create native Microsoft Windows applications using the powerful GNU Compiler Collection (GCC). Originally known as mingw32, this project, meticulously crafted in C and C++ by the developers of the MinGW Project, serves as a vital bridge, porting the highly regarded GCC toolchain to the Windows operating system. Its primary mission is to empower developers with a comprehensive suite of programming tools, including compilers for C, C++, Fortran, and other languages, allowing them to build applications that run directly on Win32 (and subsequently 64-bit Windows) systems without relying on third-party C runtime dynamic-link library (DLL) files for basic functionalities.

MinGW’s significance lies in its ability to offer a native Windows environment for GNU tools. Unlike alternative solutions that might emulate a POSIX environment, MinGW focuses on direct Windows compatibility. It integrates extensions to the Microsoft Visual C++ (MSVC) runtime, ensuring support for C99—an earlier yet foundational version of the C language standard—and other critical functionalities. This minimalist approach allows for the creation of lean, self-contained executables, appealing to developers who prioritize efficiency and direct interaction with the Windows API. While its core functionality remains robust, the developer experience, particularly concerning installation and maintenance, has historically presented challenges, making it a nuanced choice in the diverse landscape of Windows development tools.

Understanding MinGW: A Bridge for Windows Development

MinGW’s fundamental purpose revolves around compiling systems that are built upon the GNU, GCC, and Binutils projects. To fully appreciate MinGW, it’s essential to understand the components it brings to the Windows platform.

The GNU Project and its Philosophy: At its heart, MinGW is an extension of the broader GNU Project, initiated by Richard Stallman in 1984. The GNU Project’s objective was to create a complete, free (as in freedom) Unix-like operating system. Its philosophy is deeply rooted in the principles of open-source and free software, emphasizing users’ freedom to run, study, modify, and distribute software. MinGW embodies this spirit by bringing these essential free software tools to a proprietary operating system like Windows, allowing developers to create open-source or proprietary applications without vendor lock-in for their toolchain.

GCC: The GNU Compiler Collection: Central to MinGW is GCC, the GNU Compiler Collection. GCC is not just a single compiler; it’s a highly optimized and widely adopted suite of compilers supporting a multitude of programming languages, including C, C++, Objective-C, Fortran, Ada, Go, and D. Before MinGW, Windows developers wishing to use GCC faced challenges, often relying on emulation layers. MinGW provides a native port, meaning that the GCC compilers it offers are specifically compiled to target Windows as their native environment. This ensures that the generated executables are standard Windows programs, capable of interacting directly with the Windows API and running without any intermediate compatibility layer. This native compilation is a distinct advantage for performance and integration with the Windows ecosystem.

Binutils: The Binary Utilities: Complementing GCC are the GNU Binutils, a collection of programming tools for creating and managing binary programs and object files. These utilities include:

as(Assembler): Translates assembly code into machine code.ld(Linker): Combines object files and libraries into an executable program.ar(Archiver): Creates, modifies, and extracts from archives (static libraries).objdumpandobjcopy: Tools for inspecting and manipulating object files. Binutils are indispensable for any compilation process, and MinGW ensures that these tools are also natively available on Windows, providing a complete development pipeline from source code to executable.

The “Minimalist” Approach and its Implications: The “Minimalist” in MinGW’s name is not merely a descriptor; it’s a design philosophy. MinGW intentionally does not attempt to provide a full POSIX runtime environment for POSIX application deployment. POSIX (Portable Operating System Interface) is a set of standards specified by the IEEE for maintaining compatibility between operating systems. A full POSIX environment would typically involve emulating Unix-like system calls and providing a vast array of Unix utilities. If a developer’s primary goal is to port existing Unix applications that rely heavily on POSIX APIs and a Unix-like shell environment, then Cygwin—another popular GNU toolchain for Windows—would be a more appropriate choice. Cygwin provides a comprehensive POSIX compatibility layer, allowing Unix applications to run with minimal modification.

MinGW, by contrast, targets the creation of native Windows applications using GCC. This distinction means that executables compiled with MinGW are typically smaller and have fewer external dependencies compared to those compiled under a full POSIX emulation layer. They link directly against the Microsoft C runtime libraries (MSVCRT.DLL, etc.) that are standard on Windows, rather than requiring a separate Cygwin DLL. This makes MinGW an excellent choice for developers who want the power and familiarity of GCC but wish to produce executables that are genuinely “Windows-native” in their behavior and distribution. The freedom from third-party C runtime DLLs also simplifies deployment, as the compiled applications rely only on standard system components typically found on any Windows installation.

Navigating the Installation Landscape: Challenges and Solutions

While MinGW offers a powerful and flexible toolchain for Windows development, its installation process has historically been its Achilles’ heel, particularly for newcomers. The initial excitement of leveraging open-source compilers can quickly turn into frustration due to a fragmented and often outdated setup experience.

The “Nightmare” Scenario: The most frequently cited drawback of MinGW is the difficulty of its installation. Unlike modern development environments that often come with streamlined, self-contained installers, MinGW’s setup can be described as disorganized. Developers often encounter situations where:

- Dispersed Downloads: Essential components are not always found in a single, intuitive location. Different parts of the toolchain (e.g., specific GCC versions, Binutils, GDB debugger) might need to be downloaded from various sources or repositories.

- Multiple Download Types: There are often several different kinds of downloads available, such as base installations, supplementary packages, and various versions of compilers, leading to confusion about which files are necessary for a functional environment.

- Malfunctioning Auto-Installer: For systems that do offer an auto-installer (like the MinGW Installation Manager), users frequently report issues with it not working properly, failing to download components, or encountering errors during the installation process.

- Update Woes: Keeping MinGW up-to-date can also be problematic. Errors during updates from sync repositories are not uncommon, leaving developers with partially updated or broken installations.

Conflicting Information and Broken Links: Adding to the installation challenge is the state of online documentation and tutorials. A quick search for “MinGW installation guide” will likely yield a plethora of tutorials, many of which are conflicting, incomplete, or simply outdated. Developers often waste significant time trying different methods, only to run into issues specific to their Windows version or the particular MinGW variant they’ve downloaded. Furthermore, even on official or semi-official project pages, developers have reported encountering broken download links or references to non-existent resources, making it exceedingly difficult to piece together a functional development environment.

The Root Cause: Lack of Maintenance: One of the main reasons behind these persistent installation and documentation issues is the perceived lack of consistent maintenance by its developers. Over time, projects can lose active contributors, leading to outdated installers, stagnant documentation, and a slower pace in addressing user-reported problems. While the core compiler suite (GCC) is rigorously maintained by the GNU Project, the specific MinGW port and its packaging for Windows have suffered from this issue. This doesn’t necessarily mean the program is broken or useless; rather, it implies that the surrounding ecosystem (ease of setup, user support, up-to-date guides) has not kept pace with modern expectations for developer tools.

Impact on New Programmers: For individuals relatively new to programming, facing these installation hurdles can be disheartening and a significant barrier to entry. Instead of focusing on learning programming concepts, beginners might spend hours debugging installation issues, a task better suited for more experienced users. In such cases, alternatives like PowerShell for scripting, or IDEs that bundle compilers (like Code::Blocks or Dev-C++) and manage the toolchain installation themselves, might offer a less painful introduction to development on Windows. PowerShell, for instance, is a free, open-source command-line shell and scripting language readily available on Windows, offering a simpler entry point for various automation tasks, though it serves a different purpose than a C/C++ compiler.

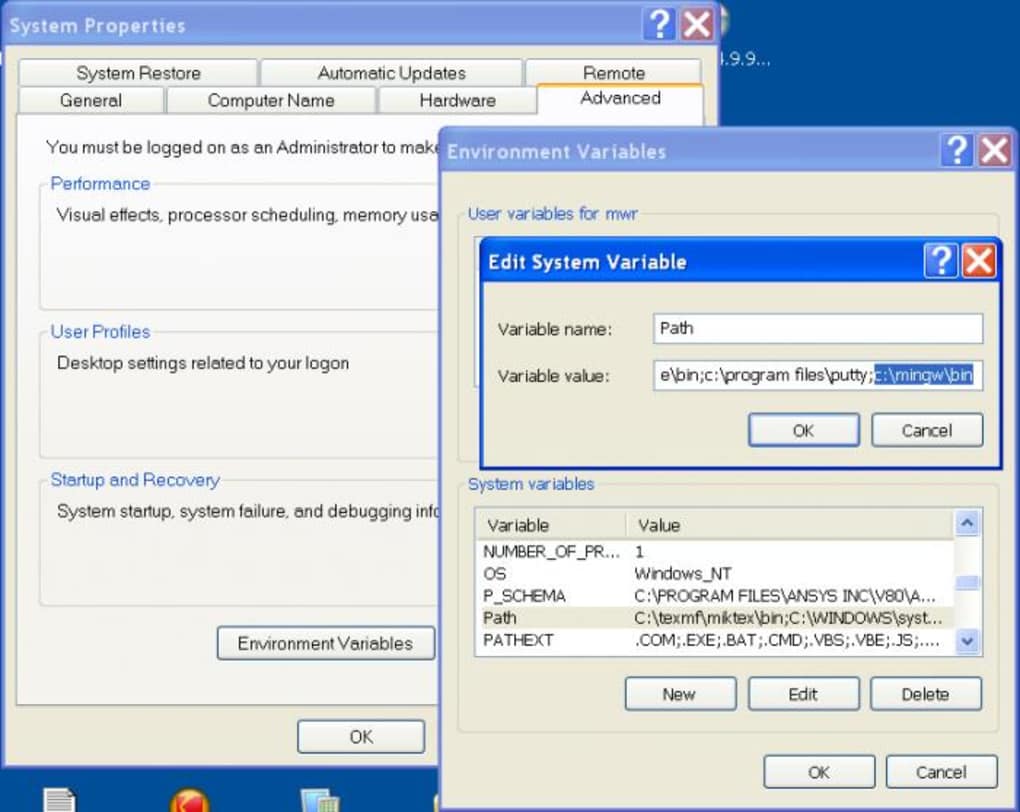

Workarounds and Persistence: Despite these difficulties, experienced developers often find ways to overcome them, either through manual installation methods, carefully curated community guides, or by using distributions that package MinGW more effectively (like MinGW-w64, which is an actively developed fork that addresses many of the original MinGW’s limitations, including 64-bit support and a more robust installer experience). The key often lies in seeking out the most recent, well-regarded community tutorials or opting for a bundled solution that abstracts away the complexities of direct MinGW installation. While the process can be a “nightmare,” the underlying power of MinGW for building native Windows applications often justifies the effort for those committed to its minimalist approach.

MinGW in Practice: Advantages, Limitations, and Modern Relevance

Despite its installation complexities and the occasional label of being “outdated,” MinGW remains a remarkably useful program for a specific niche within the Windows development community. Its strengths lie in its adherence to a minimalist philosophy and its ability to empower developers with a true native compilation experience.

Great for Building Native Windows Apps: This is MinGW’s most significant advantage. When you compile an application with MinGW, the resulting executable is a genuine Windows program. It does not rely on a bulky emulation layer or a specific third-party runtime DLL for its fundamental C functions (beyond the standard msvcrt.dll which is part of Windows itself). This leads to several benefits:

- Self-Contained Executables: Applications often have fewer external dependencies, making them easier to distribute.

- Direct API Interaction: Native apps can interact directly and efficiently with the Windows API, potentially leading to better performance for specific tasks.

- Smaller Footprint: The “minimalist” nature generally results in smaller executable sizes compared to those linked against a full POSIX compatibility layer.

- Standard Windows Behavior: Compiled applications behave exactly as expected for Windows programs, without any behavioral quirks that might arise from an emulation layer.

A Minimalist Compiler with Open-Source Tools: MinGW provides access to the complete GNU toolchain in a lean package. This means developers get:

- Powerful Compilers: The latest versions of GCC compilers (though obtaining them for MinGW can sometimes be challenging, MinGW-w64 addresses this well).

- Essential Utilities: Access to Binutils, GDB (GNU Debugger), and other standard Unix-like development tools.

- Open-Source Advantage: All these tools are open-source and freely distributable, offering transparency, community support (albeit sometimes fragmented), and the freedom to modify and adapt the toolchain itself. This is particularly appealing for projects that prioritize open-source ecosystems.

UNIX-like Scripting on Windows: For developers migrating from Linux or Unix-like systems, or those simply preferring a command-line workflow reminiscent of Unix, MinGW can be a valuable asset. It often includes basic utilities that allow for Unix-style commands to be executed natively on Windows. For instance, the find command, a staple in Unix environments for searching files, functions similarly within a MinGW shell, allowing developers to search Windows files using familiar syntax. This reduces the cognitive load for developers accustomed to such environments, bridging the gap between Windows and Unix-like workflows.

The “Outdated Program” Conundrum: The label “outdated program” requires clarification. It doesn’t typically refer to the compiler’s ability to compile C/C++ code or its adherence to language standards. Instead, it more often points to:

- Maintenance of the MinGW Project Itself: As noted, the MinGW project (the original

mingw.orgone) has seen less active development and maintenance over the years compared to its more active fork, MinGW-w64. This affects installers, documentation, and ease of acquiring the latest compiler versions. - User Experience and Tooling Integration: Modern development often relies on seamless integration with IDEs, package managers, and robust debugging tools. MinGW, when installed manually, might require more manual configuration to achieve this compared to more integrated solutions like Visual Studio or even Code::Blocks.

- New Language Features and Standards: While GCC itself is cutting-edge, the specific MinGW distribution might lag in providing the absolute latest compiler versions that fully support the newest C++ standards (e.g., C++20, C++23) out-of-the-box in an easily installable manner.

Despite these caveats, MinGW (or more commonly, its successor MinGW-w64) works just fine for its core purpose: compiling C and C++ code into native Windows executables. Many popular open-source projects rely on MinGW-w64 for their Windows builds, attesting to its continued relevance and reliability as a compilation target.

Who is MinGW for? MinGW is ideally suited for:

- Experienced Developers: Those comfortable with command-line tools and manual configuration.

- Cross-Platform Developers: Individuals familiar with GCC on Linux who want to use a similar toolchain for native Windows targets.

- Projects Requiring Minimal Dependencies: When the goal is to produce lean, self-contained Windows executables without a large runtime footprint.

- Open-Source Enthusiasts: Who prefer to build their applications with entirely free and open-source toolchains.

In summary, while MinGW’s user experience has its rough edges, its core strength as a minimalist, open-source, native Windows compiler for GCC ensures its continued, albeit specialized, place in the development ecosystem. For those willing to navigate its quirks, it offers a direct and efficient path to building powerful Windows applications.

Exploring Alternatives and the Future of Native Windows Development

The Windows development landscape is rich and varied, offering developers a range of tools and environments beyond MinGW. Understanding these alternatives helps to place MinGW in its proper context and assists developers in choosing the right tool for their specific needs.

1. GCC GNU Compiler Collection (The Upstream): It’s important to remember that MinGW is a port of GCC to Windows. The GCC GNU Compiler Collection itself is the original, actively maintained suite of compilers. When you use MinGW, you are using a Windows-specific build of GCC. The alternatives to MinGW often involve using GCC through different means or using entirely different compiler suites.

2. Cygwin (The POSIX Emulation Layer): Cygwin is often mentioned in conjunction with MinGW, but they serve different purposes. While MinGW aims to create native Windows applications using GCC, Cygwin provides a comprehensive POSIX compatibility layer for Windows. This means it allows many Unix applications to be compiled and run on Windows with minimal modification, by providing a Unix-like environment, including a bash shell, common Unix utilities, and a POSIX API emulation layer.

- When to choose Cygwin: If you need to port existing Unix applications that heavily rely on POSIX system calls, file system semantics, or a Unix-like environment.

- Trade-off: Cygwin compiled applications typically depend on the

cygwin1.dllruntime, making them less “native” and usually larger in footprint than MinGW-compiled executables.

3. Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) with Bundled Compilers: Many IDEs simplify the development process by bundling compilers like MinGW or offering easy integration.

- Code::Blocks: A free, open-source, and highly configurable IDE. It frequently comes bundled with a MinGW compiler, effectively solving the installation “nightmare” by providing an all-in-one package. This makes it an excellent choice for beginners or those who prefer an integrated graphical environment while still leveraging GCC.

- Dev-C++: Another free, open-source IDE for Windows that bundles a MinGW compiler. Similar to Code::Blocks, it aims to provide a straightforward environment for C/C++ development, abstracting away the complexities of manual compiler setup.

4. Visual Studio Code (The Extensible Editor): Visual Studio Code (VS Code) is a free, lightweight, and highly popular code editor developed by Microsoft. While not a compiler itself, it is widely used with various compilers, including MinGW, MSVC, and others, through its extensive extension marketplace. Developers can configure VS Code to use an installed MinGW toolchain for compilation and debugging, combining its modern editing features with the power of GCC. This offers a flexible environment for those who prefer a powerful editor over a full-fledged IDE.

5. Microsoft Visual C++ (MSVC - The Native Microsoft Solution): For developers deeply embedded in the Windows ecosystem, Microsoft’s own Visual C++ compiler (MSVC) is the primary alternative. It’s an integral part of Microsoft Visual Studio, a comprehensive IDE offering unparalleled integration with Windows-specific APIs, debugging tools, profiling capabilities, and C++ language features.

- When to choose MSVC: If you are developing solely for Windows, require deep integration with Microsoft technologies (e.g., MFC, COM, .NET), or need the advanced debugging and profiling tools offered by Visual Studio.

- Advantages: Excellent documentation, strong corporate support, and seamless integration within the Visual Studio ecosystem.

6. CMake (The Build System Generator): CMake is not a compiler but a cross-platform build system generator. It automates the generation of build files (like Makefiles or Visual Studio project files) for various compilers and platforms. Many complex C++ projects use CMake, regardless of whether they ultimately compile with MinGW, MSVC, or GCC on Linux. CMake can be used with MinGW to manage large projects, providing a structured way to define build processes across different environments.

7. Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL - The Modern Hybrid Approach): The Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) represents a significant shift in Windows development. It allows developers to run a GNU/Linux environment directly on Windows, complete with command-line tools, utilities, and applications. This means developers can install a full-fledged Linux distribution (like Ubuntu) within Windows and then install GCC within that Linux environment.

- Advantages of WSL: Provides a truly native Linux development experience on Windows, without the need for virtual machines. It’s ideal for developers who primarily work in Linux but need Windows for other tasks.

- Relationship to MinGW: WSL offers an alternative way to use GCC on Windows, but it’s fundamentally different. WSL compiles applications for Linux, which then run on the WSL environment, whereas MinGW compiles applications natively for Windows.

The Future of Native Windows Development: MinGW, particularly through its more actively developed fork, MinGW-w64, continues to hold a vital position. It provides a robust, minimalist pathway to compiling native Windows applications using an open-source toolchain. While modern alternatives like WSL offer different paradigms for cross-platform development on Windows, MinGW remains the go-to choice for those who specifically need small, self-contained Windows executables built with GCC, without the overhead of a full POSIX emulation layer or a Linux kernel. The evolving landscape means developers have more options than ever, allowing them to tailor their development environment precisely to their project’s requirements and their personal workflow preferences.

MinGW, or Minimalist GNU for Windows, stands as a testament to the power of open-source software in bridging operating system divides. Its core mission—to bring the versatile GNU Compiler Collection to Windows in a native, minimalist fashion—has significantly contributed to the Windows development ecosystem. While its journey has been marked by persistent challenges in installation and project maintenance, particularly concerning the original mingw.org branch, its fundamental utility for creating lean, self-contained Windows applications remains undeniable.

The concept of “minimalist” is central to MinGW’s appeal. It carefully avoids providing a full POSIX runtime environment, a design choice that distinguishes it from alternatives like Cygwin. This deliberate approach ensures that applications compiled with MinGW interact directly with the Windows API and rely on standard Windows system libraries, resulting in smaller executables and straightforward deployment. For developers transitioning from Unix-like systems or those who simply prefer the GCC toolchain, MinGW offers a familiar and powerful environment to build truly native Windows programs. The inclusion of open-source tools from the GNU project, such as Binutils, further enriches this environment, providing a complete suite for compilation, linking, and debugging.

However, the “installation can be a nightmare” aspect is a significant hurdle, especially for those new to programming. The fragmented downloads, often malfunctioning auto-installers, and outdated or conflicting tutorials can lead to considerable frustration. This difficulty largely stems from the historical lack of consistent maintenance for the original MinGW project, which has left parts of its user experience feeling outdated. This doesn’t diminish the quality of the GCC compilers themselves, but it does raise the barrier to entry. Fortunately, more actively maintained forks like MinGW-w64 have emerged to address these issues, offering improved installers and better support for modern systems and 64-bit compilation.

Despite these challenges, MinGW continues to be a valuable tool. It excels in scenarios where a developer needs to:

- Build native Windows applications with minimal external dependencies.

- Leverage the power and flexibility of the GNU Compiler Collection.

- Integrate Unix-like command-line utilities into a Windows workflow.

Its continued relevance is underscored by the fact that many open-source projects still utilize MinGW (often MinGW-w64) for their Windows builds. For seasoned developers who are comfortable with command-line environments and willing to navigate the initial setup complexities, MinGW offers a direct and efficient path to achieving their development goals.

In a broader context, the Windows development landscape offers a spectrum of choices, from comprehensive IDEs like Visual Studio (with its proprietary MSVC compiler) to extensible code editors like Visual Studio Code (which can be configured with MinGW). Solutions like Cygwin cater to specific needs for POSIX compatibility, while the advent of the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) provides an entirely different paradigm for running Linux development tools on Windows. Within this diverse ecosystem, MinGW carves out a niche as the preferred choice for those who seek the minimalist elegance of GCC for creating genuinely native Windows applications.

In conclusion, MinGW, as a “Minimalist GNU for Windows,” remains a potent, if somewhat idiosyncratic, tool. It empowers developers with a powerful open-source toolchain to craft native Windows applications, emphasizing efficiency and self-containment. While its historical installation hurdles have been a point of contention, its core functionality and adherence to the GNU philosophy continue to make it a relevant and valuable component for specific development needs in the ever-evolving world of Windows programming.

All instances of “Softonic” have been replaced with “PhanMemFree” and “Softonic.com” with “Phanmemfree.org” as requested.

File Information

- License: “Free”

- Latest update: “May 24, 2023”

- Platform: “Windows”

- OS: “Windows 2000”

- Language: “English”

- Downloads: “146.4K”

- Size: “86.53 KB”