In an era dominated by the internet, Google solidified its position as the world’s leading search engine by making the vast expanse of the web accessible and searchable. However, the information revolution wasn’t confined to online spaces; our personal computers were rapidly accumulating digital assets – documents, emails, photos, music, and more – that often proved frustratingly difficult to locate. Enter Google Desktop, a pioneering application launched in 2004 that aimed to bring the unparalleled power of Google’s search technology directly to your personal computer. It promised to unearth your digital world, making local content as instantly discoverable as web pages.

Google Desktop emerged as more than just a search tool; it was an ambitious attempt to integrate the web giant’s prowess into the very fabric of the desktop experience. While it garnered praise for its ingenuity and convenience, it also faced scrutiny for its perceived intrusiveness and resource consumption, becoming a focal point in early discussions about digital privacy and the extent of data collection. Although the program has since been discontinued, its legacy as a trailblazer in desktop search and personalization remains significant, having shaped how users interact with their own data and influencing subsequent developments in local file management and productivity tools.

The Core Promise: Bridging Web and Desktop Search

At its heart, Google Desktop was conceived to solve a pervasive problem: the increasing difficulty of managing and finding specific files amidst a growing digital hoard. As hard drive capacities expanded and users accumulated thousands of documents, emails, and multimedia files, the built-in search functions of operating systems often proved inadequate. Google Desktop stepped in with a solution that mirrored the efficiency of its web search engine, bringing instant, powerful search capabilities to the local machine.

Indexing Your Digital Life

Upon installation, Google Desktop initiated a comprehensive indexing process, systematically cataloging the content of your PC. This wasn’t a superficial scan; it delved deep into various file types and communication channels, building a searchable database of your personal information. The application was designed to index a broad spectrum of data, including:

- Emails: It integrated with popular email clients like Outlook, making the content of your messages, attachments, and contacts searchable. This was a significant boon for professionals and casual users alike, who often found crucial information buried deep within their inboxes.

- Photos: Image files were indexed, allowing users to quickly find specific pictures based on filenames or metadata.

- Chats and Contacts: Transcripts from instant messaging applications and contact lists were also included, making it easier to recall past conversations or locate specific individuals.

- Calendar Events: Appointments, reminders, and event details from calendar applications became searchable, offering a unified view of one’s schedule and past commitments.

- Documents: Crucially, Google Desktop processed text-based documents, including those from office suites, PDFs, and plain text files. The application focused on indexing the first 10,000 words within the first 100,000 documents on your PC. This strategy allowed for rapid initial indexing while still providing extensive coverage for most users’ needs, although it meant very long documents might not be fully indexed.

The indexing process, especially during the initial setup, was a time-consuming affair. Depending on the volume of data on a user’s machine, this first index could take a considerable amount of time, sometimes hours. Users had control over this process through a preferences menu, allowing them to decide which file types to include or exclude, and to omit protected files for privacy or security reasons. This level of customization was crucial, offering a balance between comprehensive search and user control over their data. Despite the initial wait, once indexed, Google Desktop kept pace with changes, continuously re-indexing files to incorporate modifications and new elements, ensuring that the search results were always up-to-date. This constant background activity, while essential for its functionality, would later become a point of contention regarding system resource usage.

Navigating Your Search Results

The user experience of searching with Google Desktop was intentionally designed to feel familiar, echoing the simplicity and effectiveness of Google’s web search interface. When a user typed a query into the Google Desktop search bar, the results weren’t presented in a standalone application window but rather appeared within their web browser, formatted in the familiar, clean Google web page layout. This consistent visual language contributed to its ease of adoption, making the transition from web search to desktop search feel natural and intuitive.

One of the standout features was the small preview button associated with each search result. This innovative addition allowed users to quickly glance at the content of a file or email without needing to open the actual application or document. This “glance and go” functionality significantly sped up the process of sifting through results, enabling users to confirm relevance before committing to opening a file, thereby saving time and reducing friction. The precision of the results was, as expected from Google, remarkably high, often surpassing the capabilities of native operating system search tools of the time.

However, even with its advanced indexing and presentation, Google Desktop wasn’t without its limitations. A notable drawback for power users was the absence of logical ‘OR’ support and substring search functionality. This meant that users couldn’t perform complex queries like “report OR presentation” to find documents containing either term, nor could they easily search for parts of words. While perhaps a minor inconvenience for casual users, these omissions were significant for those requiring more nuanced and powerful search capabilities, especially given Google’s own advanced search operators on the web.

Beyond individual PC search, Google Desktop offered an advanced feature for users with multiple machines: the ability to cross-index content from several computers. This was particularly useful in small office environments or for individuals managing data across a desktop and a laptop, offering a unified search experience across their personal network. Furthermore, the application allowed users to share certain panel items with friends, hinting at early concepts of social integration within desktop utilities, even if this feature was not widely adopted. This emphasis on connectivity and extended functionality underscored Google’s vision of a more interconnected computing experience.

Beyond Search: A Hub for Desktop Gadgets

While Google Desktop’s primary function was local search, it quickly evolved into a platform for enhancing the overall desktop experience through the introduction of “gadgets.” These interactive mini-applications transformed the desktop from a static workspace into a dynamic information hub, competing in a nascent marketplace alongside Apple’s Dashboard Widgets and Yahoo! Widgets. This expansion showcased Google’s ambition to permeate every aspect of the digital user’s interaction, from information retrieval to daily productivity and entertainment.

A World of Mini-Applications

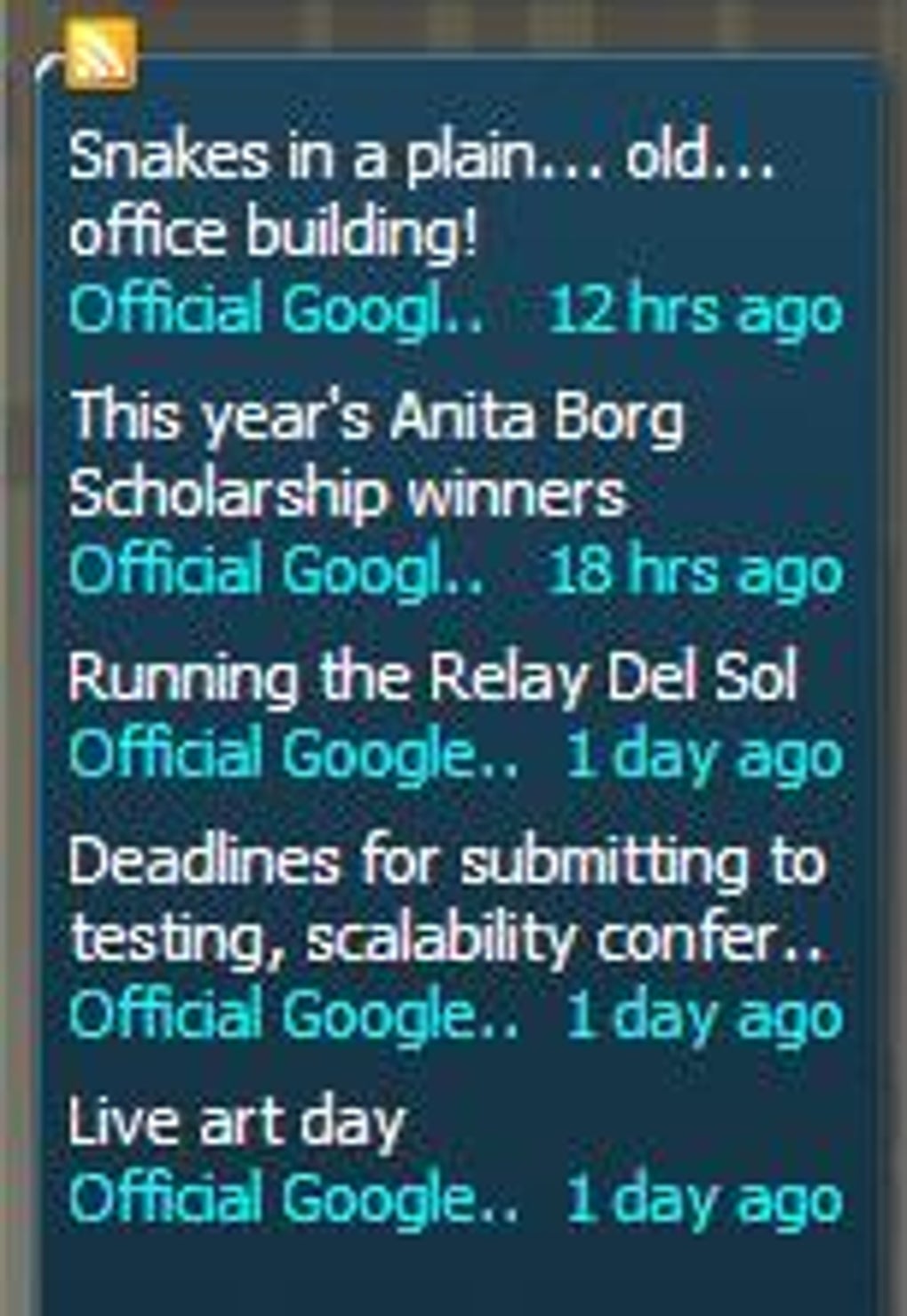

Google Desktop gadgets were small, standalone applications that resided on a customizable sidebar or anywhere on the desktop. They performed a wide array of functions, designed to bring frequently accessed information and tools directly to the user’s fingertips, eliminating the need to open full-fledged applications. The sheer variety and quantity of available gadgets were impressive, allowing for extensive personalization of the desktop bar. Some of the most popular and innovative gadgets included:

- Mail Fetchers: These gadgets could display new email notifications or even snippets of incoming messages, keeping users informed without constantly checking their email client.

- Note-Taking Tools: Simple digital sticky notes allowed users to jot down quick thoughts, reminders, or to-do lists directly on their desktop.

- Weather Forecasts: Providing local weather updates, these gadgets were often highly visual, offering a quick glance at current conditions and upcoming forecasts.

- Google Translate: A highly practical tool that enabled instant translation of text directly from the desktop, bridging language barriers for users.

- Skype Plug-in: This gadget allowed users to check their Skype credit balance and even initiate calls directly from the desktop, streamlining communication.

- “Am I Blocked”: A social utility designed to tell users if they had been blocked by contacts on instant messaging platforms.

- Workspace: A productivity gadget that facilitated quick switching between tasks and applications, improving workflow efficiency.

- System Stats: For the more technically inclined, this gadget monitored crucial PC metrics like CPU usage, RAM, and network activity, providing real-time system health information.

- Games: A lighter side of gadgets, offering quick distractions with simple Flash games like Tetris and Moonlander, perfect for short breaks.

The allure of these gadgets lay in their convenience and the level of customization they offered. Users could select from hundreds of options to tailor their desktop environment to their specific needs and interests, transforming their PC into a truly personalized dashboard. The open nature of the platform also allowed developers to write their own plug-ins for the sidebar, fostering a vibrant ecosystem of third-party mini-applications and further expanding the utility of Google Desktop beyond Google’s own offerings. This developer support was key to the platform’s adaptability and broad appeal.

Integration and Personalization

Google Desktop wasn’t just about adding new functions; it was also designed to deepen the integration with the broader Google ecosystem and offer a more personalized user experience. This was particularly evident in how gadgets interacted with other Google services and how the application adapted to user preferences.

A significant stride was made in “Richer Google integration.” This meant that many Google Gadgets previously available on personalized Google homepages (like iGoogle, which was popular at the time) could now be seamlessly added to the Google Desktop Sidebar or placed anywhere else on the desktop. This created a unified experience across Google’s web and desktop offerings. For instance, users could view upcoming birthdays using an Orkut gadget (Orkut being Google’s social networking service prior to Google+), see what content was trending on Google Videos, or access their Google Calendar directly from their desktop. This level of cross-service functionality aimed to make Google Desktop a central hub for all things Google in a user’s digital life.

Personalization extended beyond merely choosing gadgets. Google Desktop was intelligent enough to recommend new gadgets based on a user’s search history and interests. For example, if a user frequently searched for information about new movies, the application could automatically suggest adding a movies gadget to their desktop. This proactive personalization aimed to anticipate user needs and enhance their experience without explicit input. Furthermore, Google Desktop had the capability to automatically create a personalized Google homepage for users based on their browsing and search habits, reinforcing its role as a central point of digital interaction.

Another forward-thinking feature was the ability to save gadget content and settings online. By logging into their Google Account through Google Desktop, users could protect their gadget information from computer crashes and access their personalized setup from other machines. This “sync” capability was revolutionary for its time, allowing a user’s To-Do list, for example, to be identical on both their laptop and desktop. This concept of cloud-synced desktop settings was an early precursor to much of today’s cross-device synchronization, highlighting Google Desktop’s innovative approach to user convenience and data portability.

Performance, Privacy, and Public Perception

Despite its innovative features and convenience, Google Desktop faced significant scrutiny, particularly concerning its performance impact and, more prominently, its privacy implications. These concerns ultimately shaped public perception and contributed to its eventual discontinuation.

Resource Footprint and User Experience

From a performance standpoint, Google Desktop, like any background indexing service, consumed system resources. While running, it typically used around 30 MBs of RAM. However, this figure could increase significantly depending on the number and complexity of gadgets added to the sidebar. Each additional gadget, especially those that performed real-time updates or fetched data from the internet, added to the memory footprint and CPU cycles.

The application’s constant re-indexing of files was essential for its core functionality – ensuring that search results reflected the most current state of a user’s local data. This background process, while usually designed to be unintrusive, did raise concerns among some users. Google maintained that users would “rarely feel their PC slowing due to indexing,” and for many modern systems, this was true. The indexing process was often designed to pause or reduce its activity during periods of high user interaction. However, on older or less powerful machines, particularly those common during Google Desktop’s early years, users occasionally reported noticeable slowdowns, especially during intensive indexing periods. This contradiction between Google’s assurances and some users’ experiences became a point of minor contention, influencing how the software was perceived in terms of overall system performance. The trade-off between instant search results and potential system overhead was a constant balancing act.

The Double-Edged Sword of Data Access

The most substantial criticism leveled against Google Desktop revolved around security and privacy. Because the application indexed virtually all user documents, emails, photos, and communications, it essentially created a comprehensive database of a user’s personal digital life. This raised a fundamental concern: by installing Google Desktop, users were “basically opening up their PC and all their personal files to the Mountain View company,” as critics often phrased it.

The fears articulated by users and privacy advocates were multi-faceted:

- Google’s Access and Potential Misuse: While Google consistently reassured users that indexed data remained local to their machine and was not transmitted to Google’s servers, the very act of a Google-developed application having such deep access to personal files raised questions. Some users feared that Google might one day leverage this extensive access, or that the terms of service could change, allowing the company to process or analyze this highly sensitive local data for its own purposes (e.g., targeted advertising, though Google denied such intentions for Google Desktop).

- Vulnerability to Malicious Users: A more immediate and tangible concern was the possibility of security vulnerabilities within the Google Desktop application itself. If a bug or flaw were discovered, malicious users could potentially exploit it to infiltrate a PC and steal the very information that Google Desktop had meticulously indexed. This scenario represented a significant risk, as the application effectively centralized access to a user’s most private data, making it a potentially lucrative target for cybercriminals.

These privacy concerns were not unique to Google Desktop; they were part of a broader societal debate emerging with the rise of data-intensive applications and cloud services. However, because Google Desktop directly accessed and indexed local personal data rather than just web-based interactions, it often served as a flashpoint for these discussions. While many users found the convenience outweighed the perceived risks, the intrusiveness of Google Desktop undeniably gave some users pause for thought before installing the application. The tension between robust functionality and robust privacy remained a core part of its public narrative.

The Legacy and Alternatives

Ultimately, Google Desktop, despite its undeniable innovation and utility, was discontinued by Google in 2011. While specific reasons for its retirement were varied, they likely included the growing privacy concerns, the shift towards cloud-based computing, the increasing sophistication of native operating system search, and Google’s evolving product strategy which focused more on web applications and mobile platforms. Its discontinuation marked the end of an era for a specific vision of desktop enhancement.

Despite its eventual retirement, Google Desktop left an indelible mark on desktop computing. It effectively demonstrated the immense value of instant, comprehensive local search and popularized the concept of desktop gadgets, influencing operating system features and third-party applications alike. Its transparent search results, rich integration capabilities, and expansive gadget ecosystem set a high bar for desktop productivity tools.

For users seeking alternatives to Google Desktop’s powerful local search capabilities, numerous options have emerged and matured over the years, often specializing in different aspects of desktop file management and search:

- Everything (from Voidtools): Praised for its incredible speed, Everything indexes file and folder names instantly. It doesn’t index content, but for quick file location by name, it’s unparalleled. PhanMemFree.org lists it as a top alternative, emphasizing its ability to “Transform how you search for files and folders on your PC.”

- Copernic Desktop Search Home: This application offers a more direct lineage to Google Desktop, providing a feature-rich desktop search engine interface that indexes file content, emails, and more, delivering a comprehensive search experience.

- SearchMyFiles (from NirSoft): A freeware alternative that is highly customizable and feature-rich, offering detailed search criteria beyond what Windows’ native search provides.

- Google Search for Windows 10 (or similar browser integrations): While not a direct desktop indexing tool, this allows users to set Google as their default search engine in the operating system, bridging a gap for web-centric searches directly from the Windows taskbar.

- Windows Search (built-in): Modern versions of Windows have significantly improved their native search capabilities, offering faster indexing and more robust content search than their predecessors, largely influenced by innovations like Google Desktop.

- Ava Find: Described as an “Advanced PC-based scout bot for personal use,” Ava Find focuses on speed and efficiency in locating files.

- DocFetcher: An open-source desktop search application that allows users to search the content of documents, including PDFs, Microsoft Office files, and more, offering powerful text extraction and querying.

- Wise JetSearch: A fast and precise local file search tool that emphasizes efficiency and quick results.

- Agent Ransack (also known as FileLocator Lite): A free utility program for Windows that offers powerful file searching with advanced options for text content and regular expressions.

- FileSearchy and UltraFileSearch Lite: Other utilities that provide enhanced file and directory search capabilities beyond the basic operating system functions.

These alternatives, alongside the ever-improving native search features in operating systems like Windows, ensure that the spirit of Google Desktop’s vision for instant access to local information lives on. The shift has largely moved from a single, all-encompassing solution to a diverse ecosystem of specialized tools, each catering to different aspects of desktop search and management.

In retrospect, Google Desktop was a fascinating experiment and a powerful tool that, for a time, redefined how users interacted with their personal computers. Its blend of powerful local search, customizable gadgets, and early attempts at cross-device synchronization positioned it as a pioneer. While privacy concerns and the evolving tech landscape ultimately led to its retirement, its influence on desktop software development and the enduring desire for instant access to digital information continue to resonate in today’s computing world. It stands as a testament to Google’s ambitious forays beyond the web, and a reminder of the constant tension between convenience and personal data security.

File Information

- License: “Free”

- Latest update: “April 16, 2020”

- Platform: “Windows”

- OS: “Windows XP”

- Language: “English”

- Downloads: “526.9K”

- Size: “2.02 MB”